I have gravel in my elbow. It is permanently imbedded just beneath a small scar there, and sometimes reminds me of its presence if I hit it just so. That gravel-laced scar also affirms my memory of what caused it. I was about eleven, and was racing my bike down a street that was outside of the boundary laid down by my parents. As I approached an intersection, a car pulled out in front of me and, in a panicked effort to avoid it, I wrenched the handlebars and ended up sprawled in the street, feeling the immediate sting of a bloody gravel-ravaged elbow and the fear of my disobedience being discovered. The gray scar that remains half a century later is proof that my memory of that afternoon is on point.

Scars Are Story Tellers

I have scars that tell other stories, too. A tiny one on my right pinky finger preserves a memory of playing tennis with my mother and being sliced by a rogue wire sticking out of the cable that supported the net. A four-and-a-half-inch scalpel-precise one on my stomach recalls an emergency abdominal surgery almost twenty years ago. And a three-inch line flanked by the evenly spaced puncture wounds of stitches on my thigh reminds me of a cancer I survived a little over a decade ago. Each scar is proof of stories in my life that may otherwise have been lost to the murkiness of memory. But like the vestigial rubble of civilizations long past, scars are the proof that what may only vaguely be remembered really and truly happened.

My gravel-laced scar is a reminder of the consequence of one of many incidences of my willful disobedience as a child. The others are merely indicative of life in a fallen, pain-laden world, where sin infects and affects everything. Scars are story tellers, and prove the veracity of the stories they tell.

Jesus’ Scars

I’m sure Jesus had plenty of scars too. He was a rural guy living a rural life in a rural environment. He lived in a rough and rugged part of the world in a turbulent time in history. He was a builder, most likely cutting stones for a living. He traversed dusty, rocky paths in sandals.

However, the most poignant scars on Jesus’ body told the greatest of his stories, indeed the greatest of all stories. And though the wounds were inflicted while he lived and ultimately led to his death, their scars remained on his body after he was raised. God saw fit to preserve the horrific scars of the scourge and crucifixion on the resurrected body of Christ.

You would think the glorified body would be pristine and free of the memory of the suffering and pain Jesus endured. In an article for Desiring God, David Mathis wrote:

Would we not expect that such an upgrade — from a perishable body designed for this world to an imperishable body designed for the next — would mean he would no longer bear the marks of suffering in this world? We might assume the Father would have chosen to remove the scars from his Son’s eternal glorified flesh, but scars were God’s idea to begin with. He made human skin to heal like this from significant injury. Some of our scars carry little meaning, but some have a lot to say, whether to our shame or to our glory, depending on the injury. That Luke and John testify so plainly to Jesus’s resurrection scars must mean they are not a defect, but a glory.

Jesus’ scars were a glory because they served as proof of the veracity of what the disciples witnessed. When Christ’s followers scattered after his death, they must have been profoundly frightened and confused. Surely this God-Man, whom they followed for three grueling years, couldn’t have been mistaken—or worse, an evil deceiver. Didn’t he tell them he was the Messiah? Wasn’t he the One who was supposed to deliver them from millennia of oppression and hardship? Wasn’t he the Lord’s Anointed foretold by the prophets? They had been so sure (Jn.1:41, Mt. 16:15-16). But now he was dead and they were in hiding. How could they have fallen victim to such a spectacular deception?

The Scars Were the Proof

But in the end, the scars were the proof. John 20:18-20 says,

Mary Magdalene went and announced to the disciples, “I have seen the Lord.” On the evening of that day, the first day of the week, the doors being locked where the disciples were for fear of the Jews, Jesus came and stood among them and said tho them, “Peace be with you.” When he had said this, he showed them his hands and his side. Then the disciples were glad when they saw the Lord.

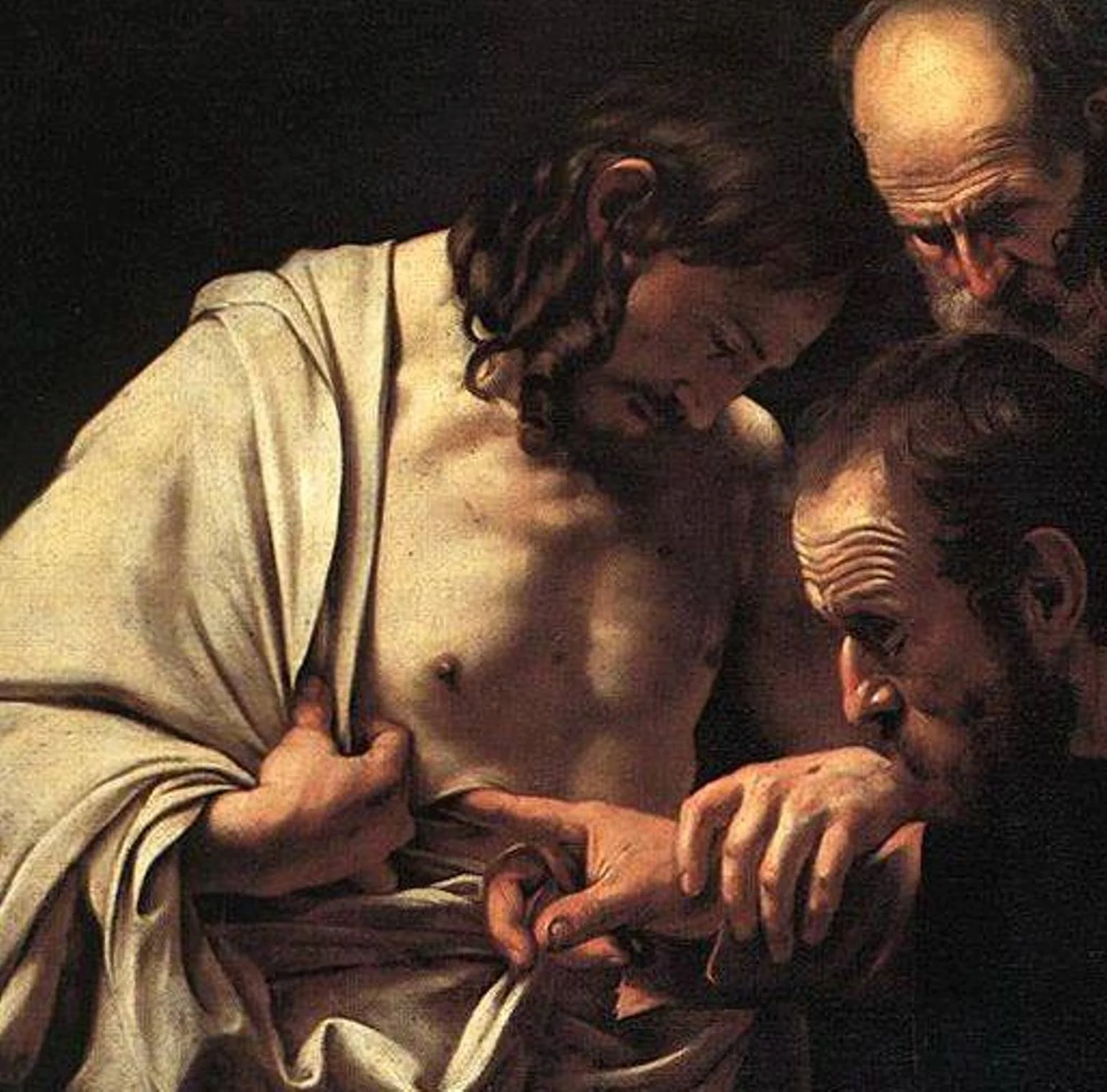

And then there was Thomas, always and forever bearing the bad rap of being the consummate doubter. John 24:26-28 recalls:

Now Thomas, one of the twelve…was not with them when Jesus came. So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord.” But he said to them, “Unless I see in his hands the mark of the nails, and place my hand into his side, I will never believe.” Eight days later, his disciples were inside again, and Thomas was with them. Although the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you.” Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side. Do not disbelieve, but believe.” Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God!”

I can’t say I wouldn’t have felt exactly the same way as Thomas. The situation was emotionally charged. The disciples’ claims were incredible. He simply wanted tangible evidence, and Jesus used his scars to give it. Jesus did not rebuke Thomas. He didn’t scold him for not believing. In his kindness he used those appalling scars as proof, and Thomas believed.

The scars on our bodies are reminders of a sinful world where pain and suffering abound. The scars on Jesus’ body affirm the story that he, the sinless man, the spotless Lamb, the condescended Creator of the universe, bears the proof of our healing, our rescue, and the assurance of a future where the only scars that remain are those wounds of love on the body of our resurrected Lord.